I. Culture in Conversation: Yusuf Tolga Ünker, Artist, Researcher

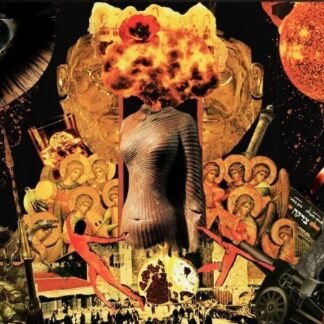

“There is safety in viewing the black and white photos from the Holocaust era. When we see the haunting eyes and faces of the tormented and tortured souls who were victimized by Nazi brutality, we can distance ourselves from the horrors that befell them due to the old look of those black and white images.” Against Oblivion Exhibition, October 2020

First, tell us a bit about yourself, your background and where you are from?

I’m an artist from Istanbul, and was born into a family of artists. My father Aykut Ünker is also a painter who started his art career at quite a young age. He was awarded his first prize in 1968, in the Young Artists Competition in Bulgaria. My mother and my father greatly impacted me in developing a passion for the arts, as well as my sister, who is a professional opera singer. They greatly supported us in our career paths. My mother also served as a great source of inspiration, as she encouraged us with her deep interest in art. I graduated from a specialized art high school, and did my Bachelors and Masters degrees at Mimar Sinan University in painting. I was a teacher for a while, however I wanted to continue my career path in academia. Since 2012, I’ve been an assistant researcher in the graphic design department at Maltepe University.

When did you first become interested in Jewish history and culture, and when did it first begin expressing itself in your art?

My interest in Jewish history and culture was first sparked in middle school when I started watching documentaries about World War II produced by the BBC. In high school I read Mein Kampf. The horrendous hate and statements against the Jewish people made me curious, and led me to research the Holocaust. I was already colorizing photos of other subjects in high school, and in university I continued my research on World War II and Jewish culture, which ultimately led me to begin colorizing photographs from the Holocaust.

Can you explain the inspiration and motivations behind you and your wife’s recent exhibition of colorized images from the Holocaust, Against Oblivion?

First of all, it’s important to note that my wife has contributed to, and helped me with my other exhibitions as well. As we well know, the reactions to works on this subject are not always positive, and my wife provides me with constant moral support and encouragement. She also supported and helped me during the preparation of this exhibition. The exhibition was curated by Jens Rusch, a well known German curator. The photographs in this exhibit were selected and curated from the private collection of an individual named Norbert Podlesny, an author on the subject of the Holocaust.

The subjects in these photographs are mostly from the ghettos; People discriminated against, and held captive in their own neighborhoods, or forced to live in the rundown areas of the city. These images show their lives in what we can accurately refer to as “open air prisons.” While the photographs from previous exhibitions were chronologically capturing the events of the Holocaust, these photographs show the daily life in the ghettos, giving us a glimpse into the routine and hardships of the individuals. For example, it is possible to see people plucking weeds from between stones by force, and other similar jobs that were imposed on them as indentured servants of the Nazi regime. This exhibition shows that the Holocaust is not limited to concentration camps, but to the minute aspects of daily life.

Do you have any connection to the Jewish community in Turkey? How have they received your work?

After I had my exhibition of colorized photographs from the Shoah in Florida, I wanted to exhibit it in Istanbul as well. The Jewish community gladly helped actualize the two exhibitions in Istanbul. These shows were hosted by The Quincentennial Foundation Museum of Turkish Jews, and curated by the museum manager, Nisya Isman Allovi. Afterwards, I made a third exhibition at the Ulus Jewish School of Istanbul, with the intention of bringing this education and empathy to the younger generation. They expressed their appreciation and thanked me for my work, thus building a good connection with the local community.

How is your work received in Turkey? Would you say that the general consumer of art is interested in Jewish culture or history?

Some people try to connect my work to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. However the events in my works and restorations are purely historical, and not meant to make a political statement. We should, and must be able to separate these two issues. Even though some people have made negative comments on my work because of this, I have mostly received positive feedback. I don’t think there is a general interest for Jewish culture or history in Turkey. I can see that I am moving forward on my own on this subject in the art world, and I want to turn the material I have into a book in order to reach a broader audience, and communicate with a variety of different communities.

What do you think the most valuable lessons are that you’ve learned from your work with Holocaust photography, or Jewish visual culture? How can this be used for progressing and reviving arts and culture?

While this small nation of people, who were scattered around the world for ages, suffered a great deal of pain, violence, and genocide, they did not collapse or disappear. Instead they jumped back on their feet even stronger, and managed to return to their ancestral homeland as one. To build a peaceful world, we have an obligation to learn from the evils of the past and teach this to others. I believe that the best method that can be utilized to do this is through art, and art education.

Are there any major Jewish artists or thinkers who have influenced you, either in your work, or in your worldview? If yes, how so?

As for those who have influenced me, one of my largest artistic influences is surely Isidor Kaufmann and Alois Heinrich Priechenfried, whose works and lives have led me down the rabbit hole of connecting my art and colorization to Jewish history. I constantly look for more reading material related to their works, and dream of seeing their art in person, in the various museums and galleries in which they are housed.

What are some of the current upcoming projects you are working on?

Right now, I am working on my thesis, a short film project on the subject of the Holocaust, of which more details will be available in the near future. I don’t want to let out too many surprises ahead of time.

Are you hoping to make any collaborative works with Jewish or Israeli artists, and if so, what kind of projects are you hoping to build?

One of my hopes is that after the pandemic, I would like to plan some kind of an event related to this subject material of the Shoah, with multiple different artists. My vision is a cross-cultural project related to the Holocaust, or other aspects of Jewish history, and cultural interactions between peoples. One such event that I hope to plan, is an interactive event where Holocaust survivors could share their experiences and stories, while their images become colorized as a backdrop, adding “life” to their historical legacy as it’s spoken. The ultimate purpose of these artistic projects that I’ve developed, and hope to implement in the future, are to educate those who know nothing of the Holocaust, and to combat the varied ways that antisemitism still permeates in the world. One needs simply to open their computer to any social media outlet, and find an array of vile and rampant conspiracies, ranging from political conspiracies of Jewish subversion, to Jews being the servants of Satan, aliens, which only scratches the surface of absurdity there is to find. Art can be a key tool in eliminating such ignorance and hate from the world, and communicating the intricate history and cultures of the Jewish people.

Additionally, I would love to work on cross-cultural art events and exhibitions with Israeli artists, as a method of building bridges and peaceful interactions between the Turkish and Israeli people. To conclude, I hope that this colorization project related to the Holocaust, and understanding history in general, can be a starting point of building a peaceful and cooperative vision for the future.

Selected Colorizations and works of Yusuf Tolga Ünker, and Fikriye Kesti Ünker:

Link to the Online Exhibition Against Oblivion on the platform Kunstmatrix, which offers an interactive digital tour to see additional colorized works of Yusuf Tolga Ünker, and his wife, Fikriye Kesti Ünker.

https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en/exhibition/2686287/gast-ausstellung-yusuf-tolga-%C3%BCnker

Link to the Youtube Video on the Channel of Curator Jens Rusch: