A Letter to Democracy,

It seems, among one of the more careful and egregious attributes of the artist, is to be consistently and miserably misunderstood. Words of light turn weighty as lead, and passionate and excited expressions ward off once-interested crowds of liberals engaged in “the humanities” and starry-eyed “romantic companions.” An exhausting cliché, as repetitive and tired as a David Lynch film.

The alternatives are silence or madness, equally unacceptable in their cost. You don’t deserve for me to stay quiet, and I certainly don’t deserve to lose my mind for you. We’ve all been there, picture this: You tell a remarkable story of interest in how a character in a film is portrayed, or the fatal decision of a character in a book. What was Shylock intending to do with his pile of flesh? Isn’t the borderline-chauvinistic but gentle expression of sex and intimacy in Kundera’s books fascinating? You look at someone and ask them what they think about Picasso’s representation of death, and they kind of stutter and roll their eyes. Nobody wants to talk with you about the beauty of the cricket’s chirp when slowed down. Nobody cares about an obscure historical fact about Mount Ararat. They all already know, and don’t care, how you feel about capitalism. At first you’re amusing, even sexy. Dark. Willing to say things and ask things out loud that others don’t. You say what you think, and what they think. They’re captivated by green eyes, and overly-direct and tactfully tactless lexicons coolly uttered through the smoke of hand-rolled cigarettes. But, after a brief moment of time, answers become scarce. The sex appeal and the intellectual exhilaration ends. People shy away. They mistake “dark” for “heavy.” They mistake José Martí for Friedrich Nietzsche. As ugly as Diego. They mistake the cry for company and camaraderie, for the growls of isolation. Nobody has the energy to discuss the archery techniques of Babylonian Soldiers in the 5th century BCE, or the final poems of Sadegh Hedayat, or the moral ambiguity of ancient Chinese literary characters at three in the morning with you. They’ll just give you Freudian sophism, tell you that you need to “calm down.” Better get used to it.

Pipe dream. Heavy pipe. Made of lead. You were once meant for their consumption and now they shy away. Some are unnerved by you, others just grow tired. “You’re intense all the time,” cries out the hollow person, he or she who seeks constant airiness in a world which demands something more. “Sorry, but this is simply too much,” (Sorry to hear that) “Maybe we’ll talk later,” (Probably not) “Interesting idea, will answer you soon!” (They won’t). And then it always ends in them telling fond stories of you to their friends, because of course, they knew you when you were no one, when you were strange and heavy. And they will claim to have known you when you return to nothing.

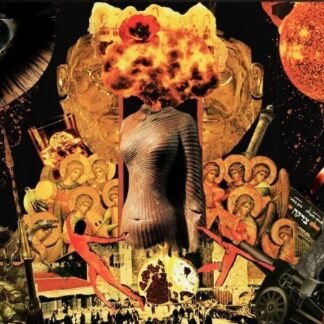

When you’re light. When you’re Jep Gambardella. When you’re Jay Gatsby. When you ask for remarks on a painting, most people will simply click a “like” on your page (as is the wonderful and horrifying nature of the social media era), and best case scenario they tell you it’s “nice,” or “beautiful.” (Which is a lot worse than being told to “calm down.”) No, it is not. Photographs of lilies are beautiful. Curly red hair is beautiful. The sunset at the marina is beautiful. Pinecones and dandelions are beautiful. Paintings expressing pain, and guilt, and light, and lust, and growth, require a slightly more clever answer.

And suddenly I’m lead, and so are you. And you feel that I’m strangling you with my “complaint.” “You’re intense all of the time.” Gatsby never gets invited anywhere, Gatsby is the invitation. And at his funeral people grew tired of his weighty, bombastic offerings of pleasure and allure. They were far too busy to answer Nick’s calls. People go to Gatsby’s Shabbat dinners, they eat his heavy food and drink his heavy leaden wine, and then they leave so they won’t have to hear his heavy stories- but they’ll tell all their friends they were at Gatsby’s feast of lead. Until they weren’t. Intense. Because lead goes to your head, “You know that Rome collapsed because of lead poisoning?” Yeah, I did. And I’m not shocked you know, either. Thanks. And on that note: the past few years, Kundera has been brewing in, and tormenting my mind, “Her drama was a drama not of heaviness but of lightness. What fell to her lot was not the burden but the unbearable lightness of being.” And I want to hate him for writing these lines and making me feel this, but I can’t. Because I can’t bring myself to hate at all. I paint because I love those people who think I’m too much, and I’ll be bold enough to speak on behalf of most of my fellow artists that they likely feel the same. Without them, how could we continue?

Lead builds character. I can simply accept that anything the artist says will be misinterpreted by the living, that they will feel alone in the hungry crowd during their lives, and that they’ll be the victim of those racing to reinterpret them, those who called them “too heavy,” once they’re gone. Can I simply accept that months bound in solitude to my apartment and psychological tempest thanks to Corona? It wasn’t really any different than “normal.” Sure, I’m heavy. But you never had to feel my weight. You didn’t have to see me. You were all too scared of an artist. You all dropped the weight. I had to feel you. I had to see you. See you looking through me, like you scan the cover of an interesting book in a second-hand bookshop, and then watch you turn around and walk away. I didn’t have the option of being afraid, even though God knows, I wanted to be.

You walked away at the slightest sign of heaviness, but I had to carry your weight of judgement. Because fear is a protection mechanism hardwired into the human psyche, and the artist disrupts the vibrations of the normative psyche, and judgement is society’s antibody.

I had to stand on the shores of jagged heaviness and stare into the ocean of judgement, and it fills me with the light which you’ve tried to steal from me. All it can do is make me want to paint for you more. The water might be refreshing after all?

And please, as I take that beautiful plunge, don’t flatter yourself into thinking this article is about you, dear reader. Do me the favour and don’t feed the animals. Let the words on my lips be “More weight.” Because my friends, nothing is heavy nor lead once you’ve looked at the stars, and tasted salt water, and heard a thousand crickets play to the tune of the chorus. The universe has voted- even the artist, hungry for life.